10/28/2019

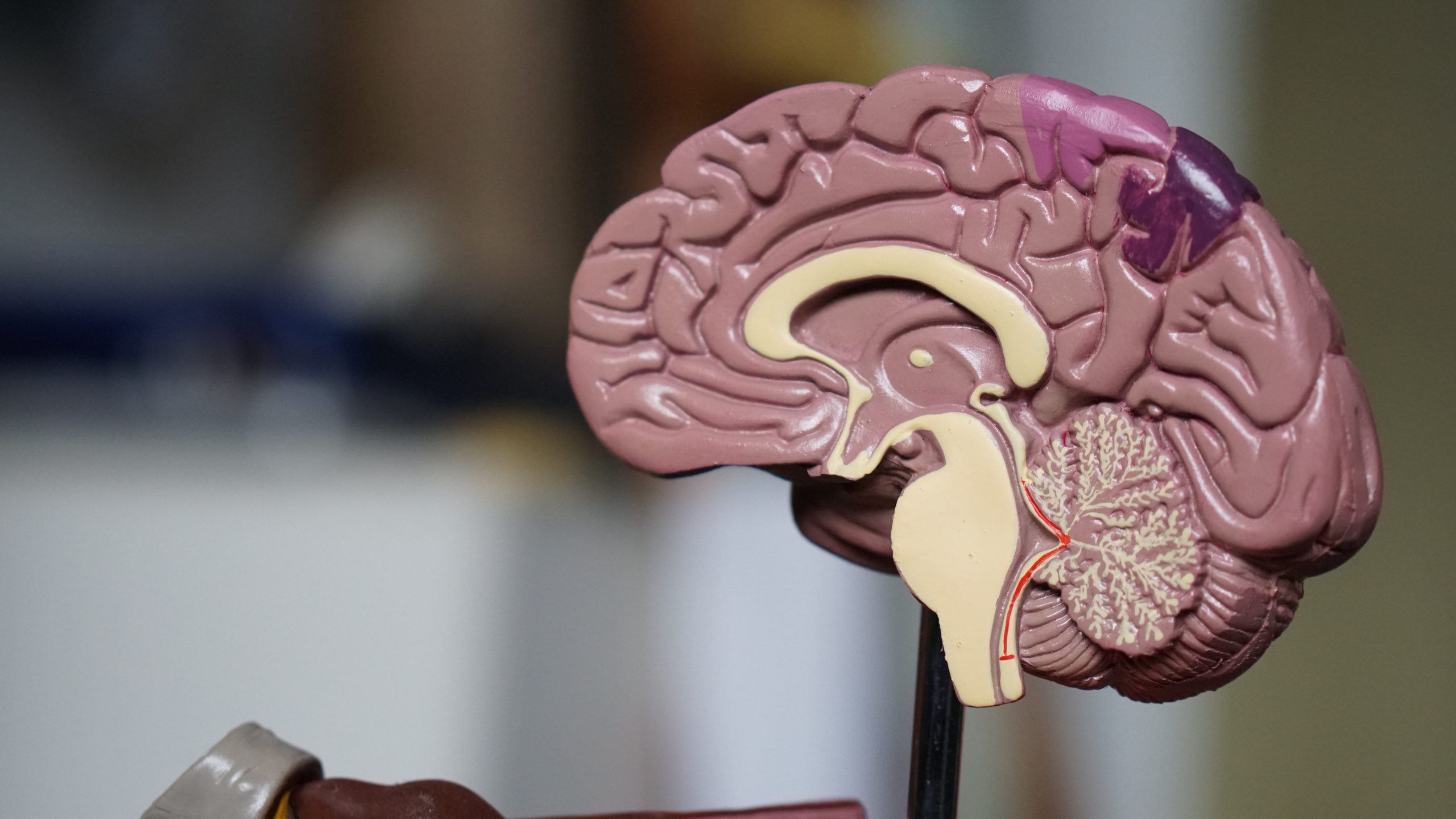

Growing human brains may sound like something out of a mad science movie, but believe it or not, scientists are able to do just that– well, sort of. Brain spheroids, also called organoids, are made of stem cells that have been carefully cultivated to grow into tiny balls of neurons. The largest scientists have been able to grow them so far is 4mm, but even at that tiny size, organoids are able to develop structures similar to those found in the human brain. Since they were first created in 2013, that important feature has helped scientists with research about schizophrenia, autism, brain development of babies whose mothers are infected with Zika virus, and several rare brain disorders.

Everything about organoids seemed great: ability to research into human brains without the pesky little issue of having to get them from an actual sentient person. However, organoids themselves may be a bit more sentient than scientists first thought. According to a Harvard study, organoids grown for 8 months were sentient enough that their neuronal networks had a measurable response when a light was shined on them, and other organoids have shown brain waves similar to those observed in premature babies. Furthermore, when human brain organoids were transplanted into mouse brains at the Salk Institute in San Diego, they were able to tap into the blood supply of the mice and create new neural connections.

That being said, organoids are still far from being able to experience pleasure, pain, or other complex states. They are nowhere near equivalent to fully formed human brains. But the discovery of this partial sentience in them was enough to make a group of scientists, lawyers, ethicists, and philosophers call for an ethical debate on organoids last year. It seems no one has really come to a consensus yet on a set of ethical guidelines to apply to organoids, but there are several questions to consider before they become more advanced. Firstly, our ethical concerns are likely greater if the organoids in question are actually sentient, but what qualifies as sentience in an organoid, and how should scientists attempt to measure it? Also, what should scientists do with organoids or the animals they have

been integrated into after the research is finished? Right now, organoids are destroyed afterward (standard practice for human tissue), but what if we determine that they are sentient? And there is also a question of data privacy: the brain tissue of organoids could reveal sensitive information, like the presence of certain brain disorders, about the person who donated the cells used to create them.

Sentience in organoids may not be possible for a while, if at all, but ethical questions like these are important to consider now, just in case it happens sooner than we expect.