Abstract

Satellite data is an indispensable resource that now constitutes a large portion of the commercial world in the United States. However, as satellite technology improves, the collection and distribution of high-quality data poses a threat to national security and personal privacy. Further, the nature of international space legislation leaves the U.S. vulnerable to collect and distribute threatening data. This calls the ethics of satellite surveillance into question. Engineers, the last barrier between companies and increasingly detailed data, must step up and consider the ethics of further developing satellite capabilities.

Introduction

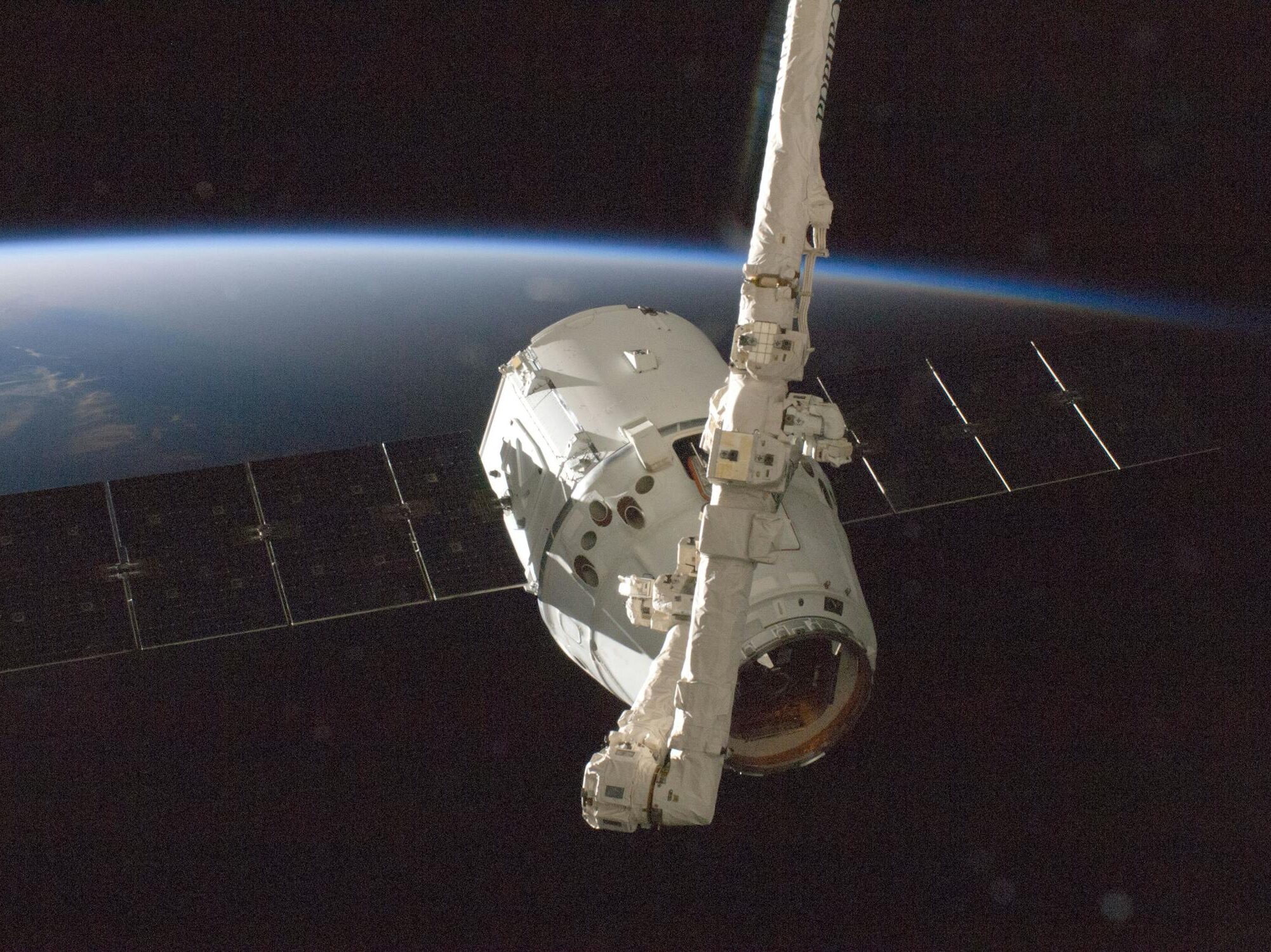

In today’s world, collecting satellite data allows companies to provide essential services to the entire globe. As of May 2023, 7,560 operational satellites were orbiting the Earth. The United States owns 5,184 of these satellites, with about 91% belonging to commercial companies [1]. Satellite ownership allows companies to provide the public with services like navigation using GPS, world exploration using Google Earth, or monitored workouts using Strava. Consumers rely on these services which are so common that the vitality of satellites often goes unnoticed. Private companies have harnessed this need for satellite technology, and they now collect massive amounts of satellite data to keep up with market demand [2]. Despite society’s increasing reliance on satellites, the public has little knowledge of and limited access to the data collected by these companies [3]. Commercial satellite surveillance will only expand in the future, putting the world’s information in the hands of any company with a satellite, a large threat to the privacy of individuals and government institutions.

The Right to Privacy: Balancing Personal Privacy and Public Areas

While the word “privacy” does not appear in the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court established the right to privacy under the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable government searches and seizures. The regulation of satellite surveillance follows the general “reasonable expectation of privacy” based upon the third party rule. This rule states that if someone knowingly exposes information to the public or turns over information to a third party, then a “reasonable expectation of privacy” cannot be established [3]. Under these guidelines, the use and distribution of data gathered by private entities, for any reason, remains legal as long as the information was obtained with consent or through public exposure. However, the lack of awareness about the information gathered by satellite surveillance muddles this reasonable expectation. The general public often fails to realize the extent of the information gathered by satellites. This creates a disconnect in the legality of surveillance, as unreasonable invasions of privacy become difficult to define [3]. Theoretically, the public understands that satellites monitor the Earth, but many forget that they can see almost all aspects of human life. This is because many people do not know much about satellites.

Current Capabilities of Satellite Technology

Satellites are the backbone of the Global Positioning System (GPS), the satellite system used to collect data for global navigation in the United States. They typically orbit near the Earth’s surface, around 500 km above the ground, and use remote sensors to continuously collect data [3]. This data includes weather patterns, radar imagery, optical imagery, atmospheric properties, location tracking, and more [3]. The most common application of this data is for Earth observation, where remote sensors deliver crucial information about surface and weather changes [4]. Companies process this into usable products, like the image of the world as seen on Google Earth or the daily forecast shown on the weather app. While satellite technology was originally developed by government entities for government use, the technology has since spread into the commercial sector. That’s because the U.S. government does not charge private companies for use of the GPS system; any company can develop chips to provide location tracking services compatible with the existing satellite network [3]. Currently, GPS covers 95% of the Earth at all times and can accurately pinpoint locations within a foot, anywhere on Earth, for any device with a compatible chip. Essentially, any person with a GPS compatible phone can be tracked, and any open backyard can be seen from space.

This was true for Curtis Croft, who was arrested in 2013 for illegally growing marijuana in his backyard. When police got a tip that Croft had been growing marijuana, they checked Google Earth to see the satellite image of his home. The photo confirmed the presence of the substance growing on Croft’s property [5]. Under the third party rule, his privacy was not violated by commercial surveillance because his backyard was considered exposed to Google Earth’s satellites [5]. As Google is a private company, their satellite surveillance was legal since it stayed within public areas. However, the presence of the plants in Croft’s backyard would have never been obtained without enhanced satellite imaging. This highlights the risks presented by the imagery and location data collected by private companies.

Further advancements in spatial resolution have only heightened these risks. Spatial resolution is the minimum distance between two objects that can be distinguished in an image [4]. The quality of all satellite images depends on the surface area captured within a single pixel. This is because a smaller area captured within a single pixel results in a clearer resolution. The resolution is limited by the area within the pixel, as images are clearest when the two are equivalent. For example, if resolution were 1 meter, then to maximize quality, the ground area measured would have to be 1 square meter. Processing this data with existing images allows companies to improve the resolution of the raw images taken by their satellites [4]. As both spatial resolution and data processing technology continue to improve, companies can collect and process high-resolution images of neighborhoods. Engineers have also developed real-time surveillance programs that are capable of showing a live feed of any visible location, albeit with compromised image quality due to the rushed processing time [3].

Risks of Satellite Technology Applied to the Commercial World

One of the most significant commercial satellite companies, DigitalGlobe, operates several satellites for the sole purpose of selling data to other private companies and governments. DigitalGlobe dominates the market and possesses extreme power over the information accessible to both the public and private companies [3]. The demand for higher-quality satellite data has enabled companies like DigitalGlobe to see more than ever before. In the past, the U.S. government was the only entity allowed to obtain full resolution data while other entities were required to collect data subsampled down to 50 centimeters resolution [6]. However, U.S. regulations now permit images taken by commercial satellites to be resampled to a resolution of just 25 centimeters to keep up with improved technology [5]. This means that private companies are able to collect data at a higher resolution.

This is concerning, as the collecting and sharing of private data has already resulted in breaches of personal privacy and national security. On top of selling raw satellite data imagery, real-time surveillance, or location tracking, DigitalGlobe also provides aggregated data and geospatial analysis services [3]. This aggregation of data was partially responsible for a national security breach. In 2018, a popular social media platform for athletes posted a heatmap with legally and consensually obtained details about the workouts, locations, and profiles of users. By publicizing the routes and identities of users, the app outlined the locations of several military bases. It was then relatively easy to track the movements of important personnel through a simple Google search [3]. The incident left the Department of Defense scrambling to reestablish security [3].

Although unintentional, the exposure emphasized the need for better regulation in mass satellite surveillance. Top secret information was made available to the public, but the process of collecting data, creating the heatmap, and making it publicly available was entirely legal. The overwhelming ownership of satellites by private companies has created a power imbalance where private entities now control the world’s information and security. Satellites are expensive to own and operate, so the vast majority of commercial satellites are controlled by profit-focused companies. Even when the public gains access to data, financial incentives still impact the quality and quantity of the data available [7]. Satellite legislation must limit the power and reach of the corporations that control them. With satellites capable of seeing more and more, the commercial collection and distribution of data must be regulated to protect personal privacy and national security from inadvertent public exposure. If regulation proves ineffective or unattainable, engineers must step up to reduce the consequences of the increased implementation of satellite technology. These notions of regulation are supported by space law.

Space Law: Regulating Data Collection and Distribution

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 established space as a “global commons” [6]. It states that space “shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind” and that “there shall be free access to all areas” without “national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, means of use, or occupation” [3]. These articles establish space as an area of commonality, where every state has equal right to freely explore and use its resources without interference. Space operations also follow the “open skies” concept, which permits states to freely collect and distribute data from space without the consent of the observed state [3]. In conjunction, the treaty establishes that each state has an obligation to supervise the activity of its commercial entities in space. This implies that it is each state’s responsibility to regulate the commercial market for satellite data [6]. Therefore, any commercial company can legally collect and distribute satellite data without the consent of another state as long as their operations are legal in their own state.

In the United States, companies face regulations regarding the collection and distribution of data. In addition to limiting the resolution of commercial satellite images, the U.S. also requires private companies to obtain licenses to launch and operate satellites. Under the Land Remote Sensing Policy Act of 1992, the operation of a “private remote sensing space system” requires a license from the Department of Commerce. This authority is executed by NOAA’s Commercial Remote Sensing Regulatory Affairs Office (CRSRA). When issuing licenses, the CRSRA must consult with other governmental agencies to address any national security or foreign policy concerns. However, the private space industry found these licenses burdensome and time consuming so, in May 2018, the Trump administration’s Space Policy Directive commanded that the Commerce Department revise regulations established in the Land Remote Sensing Policy Act in an effort to promote economic growth [8],[9].

The new regulations allow companies to sell images of a particular type and resolution if substantially similar images are already commercially available in other countries [9]. While the U.S. and other European countries have strict satellite regulations, other countries like India and China do not impose such regulations [10]. Therefore, foreign companies can collect, use, and distribute data that the U.S. classifies as impacting national security interests [3]. While the new regulations benefit U.S. satellite companies by increasing their ability to collect and sell data, they cannot prevent the collection and distribution of high-quality data by international companies. The pervasive impact of satellite surveillance emerges through this unregulated international collection and distribution of global satellite data. Even if national regulations improve to protect privacy and security within the United States, international law blocks them from controlling the spread of information on a global scale. As the capabilities of satellite surveillance continue to expand, the privacy issues of satellite surveillance require a solution that transcends the limitations of international law.

Engineering Privacy: Regulating Satellite Development

While private companies cannot be held to any regulations other than those within their respective countries, all engineers have an ethical responsibility to consider their contribution to the issue of satellite surveillance. The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) provides a code of ethics for engineers, which serves as a guideline for the continued development and implementation of satellite technology. In this code, engineers agree to “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public in the performance of their duties” [11]. In this statement, the AIAA recognizes that the lives, safety, and welfare of the public depend upon the professional decisions and practices of engineers. Additionally, engineers must “avoid harming others, their property, their reputations, or their employment through … unlawful or otherwise wrongful acts” [11]. Through this, the AIAA states that engineers must respect the personal property interests of others, to a higher degree than the law requires. As engineers have control over the cycle of demand for new satellite technology, they must consider the impact of their innovations on the privacy and safety of individuals and their property.

Modern satellite surveillance already diminishes personal privacy, so engineers must work to define an ethical boundary for the collection of public information. Meticulously outlining what the public domain is would provide the public with a general consensus of what information may be used against them. Engineers must commit themselves to preventing the further development and implementation of technology that breaks these boundaries of privacy. In doing so, they would restore the protection of national security and personal privacy and limit the threat of privacy invasions from the commercial industry [12]. No perfect solution exists, but controlling the development of satellite technologies allows all involved parties to better anticipate potential data risks. The power of satellite technology will continue to grow, and engineers have an ethical duty to limit its implementation to protect the privacy of everyone, from the government to the public, living under the many eyes in the sky.

By Rachel Pak Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California

About the Author

At the time of writing this paper, Rachel Pak was a sophomore pursuing a degree in Astronautical Engineering at the University of Southern California. In her spare time, she enjoys going on walks, listening to music, and reading.

References

[1] “UCS Satellite Database: in-depth details on the 5,465 satellites currently orbiting Earth, including their country of origin, purpose, and other operational details,” Union of Concerned Scientists, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/satellite-database.

[2] V. Labrador, “Development of Satellite Communication,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/technology/satellite-communication/Development-of-satellite-communication.

[3] A.T. McKenna, A.C. Gaudion, and J.L. Evans, “The Role of Satellites and Smart Devices: Data Surprises and Security, Privacy, and Regulatory Challenges,” Penn State Law Review, vol. 123, no. 591, p. 591-665, 2019.

[4] “Satellite Data: How to Use Satellite Data for Better Decision Making,” ICEYE, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.iceye.com/satellite-data.

[5] C. Beam, “Soon, satellites will be able to watch you everywhere all the time,” MIT Technology Review, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/06/26/102931/satellites-threaten-privacy/.

[6] C. Santos and L. Rapp, “Satellite Imagery, Very High-Resolution and Processing- Intensive Image Analysis: Potential Risks Under the GDPR,” Air and Space Law, vol. 44, no. 3, 2019.

[7] M. Politzer, “Why we need to think about ethics when using satellite data for development,” Devex, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.devex.com/news/why-we-need-to-think-about-ethics-when-using-satellite-data-for-development-99148.

[8] D.Morgan, “Commercial Space: Federal Regulation, Oversight, and Utilization,” Congressional Research Service, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/space/R45416.pdf.

[9] D. Schneider, “U.S. Eases Restrictions on Private Remote-Sensing Satellites” IEEE Spectrum, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://spectrum.ieee.org/eased-restrictions-on-commercial -remote-sensing-satellites.

[10] M.M. Coffer, “Balancing Privacy Rights and the Production of High-Quality Satellite Imagery,” Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 54, no. 11, pg. 6453-6455, 2020.

[11] “Code of Ethics,” American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.aiaa.org/about/Governance/Code-of-Ethics.

[12] L. Kisselburgh and J. Beever, “The Ethics of Privacy in Research and Design: Principles, Practices, and Potential,” Modern Socio-Technical Perspectives on Privacy, B.P. Knijnenburg, Springer, 2022, pp. 395-426.

Links for Further Reading

Satellite imagery augments power and responsibility of human rights groups

Harnessing the power of satellites to fight for human rights

Satellite surveillance may be less of a privacy concern than you think — for now

Read to find out why satellites aren’t the most imminent threat to our privacy

Satellite Technology: Past, Present, and Future

The little known roles that satellites play in everyday life