10/21/2024

Nearly five days before Hurricane Milton hit Florida, National Hurricane Center forecasters predicted its track within 12 miles of where the storm made landfall. Hurricane Helene forecasts were made with similar precision. Scientists with the National Weather Service and the National Hurricane Center began sounding the alarm for Helene three days prior to its landfall. The National Weather Service even sent out a “rare” news release urging the media to focus on the catastrophic nature of Hurricane Helene.

That day, Buncombe County in North Carolina declared a state of emergency due to warnings of dire storm conditions. “It is not common for the National Weather Service to use words like ‘catastrophic’ to describe forecasts,” Buncombe County Manager Avril Pinder said at a news conference. “When they do that, we should all take heed.” Unfortunately, locals did not heed the warning; out of the 130 people killed by the storm, at least 57 deaths occurred in Buncombe County. Mae Creadick, a resident of the county, said local officials had warned them about the storm through text messages, but she and her neighbors did not believe it could destroy the area.

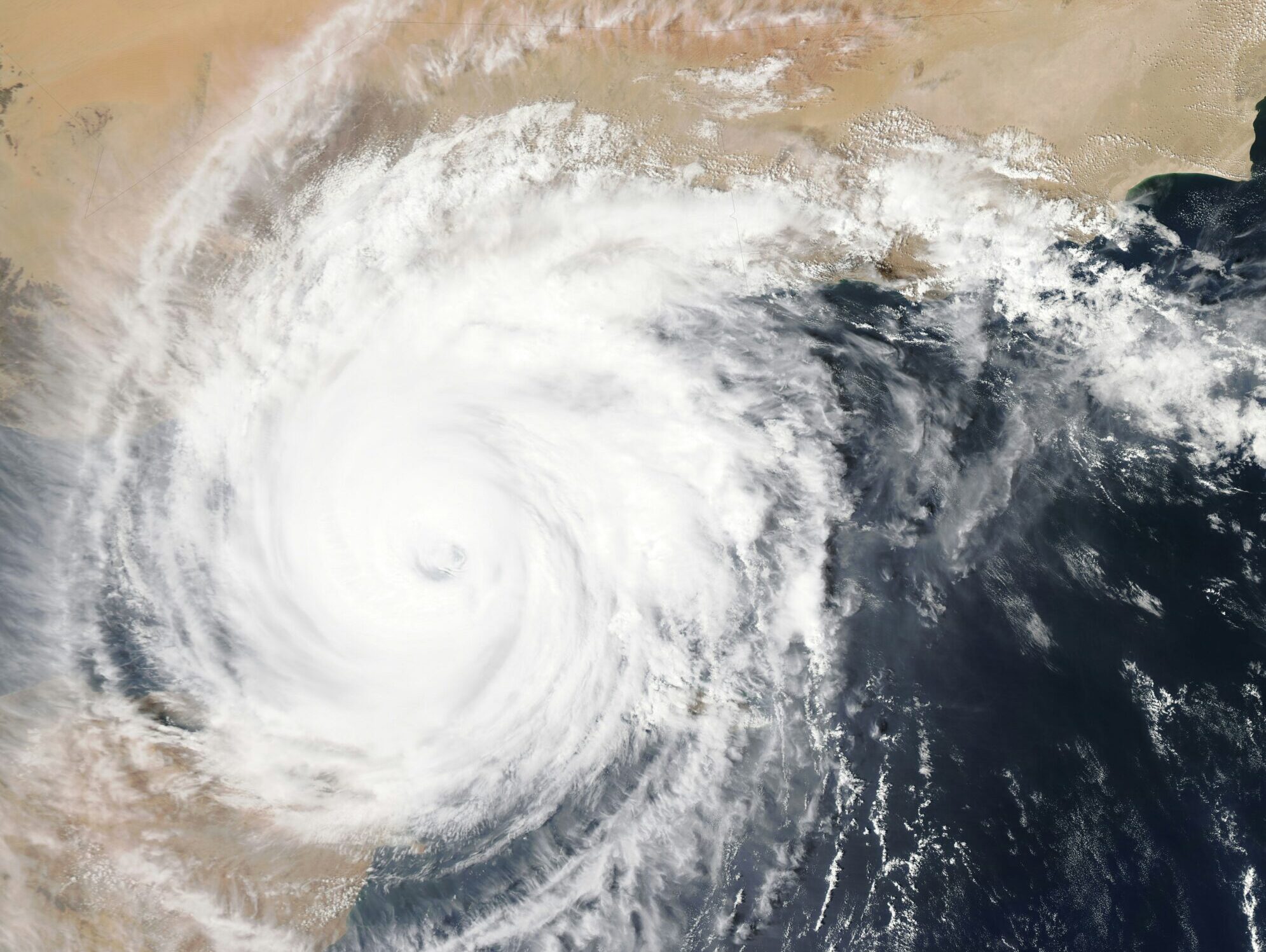

In spite of their reservations, advances in forecasting methodology and technology have made these warnings more accurate than ever before. Data from the National Hurricane Center shows the decline in track errors of storm forecasts. In the 1970s, a forecast issued 36 hours ahead of landfall had a margin of error close to 230 miles, but in the 2020s, that margin of error decreased to 57 miles. As John Morales, meteorologist and hurricane specialist for NBC, states, “nobody can say they were surprised by the landfall location and intensity of these storms.”

Despite what Matthew Cappucci, a meteorologist with MyRadar Weather and The Washington Post, calls an “almost prescient” forecast of Hurricane Milton, meteorologists have never faced so much skepticism, hatred, and conspiracy- minded pushback. Many have been accused of steering the hurricanes, and others have reported threats of violence online and even personal attacks. Cappucci says that the “uptick in conspiracy theories, especially on social media,” undermines his “ability to do [his] job effectively.”

False claims have been viewed more than 160 million times in the days following the hurricanes. Claims that the government was controlling Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton spread widely on social media platforms. One post on X with over 100,000 views claimed Hurricane Milton was “modified and manipulated” to be used as a “weapon.” Even Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, has suggested that scientists can control the weather. As Cappucci stated, “No matter how good your forecast is, it doesn’t matter if people aren’t listening.”

One part of this breakdown in communication is the link between extreme weather and climate change, which has turned apolitical groups like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) into victims of political distrust. For example, former President Donald Trump said that climate change is “one of the great scams” while referencing Hurricane Helene. As Kelli Burns, an associate professor of communications at the University of South Florida, states, “everything is politicized today — even hurricane warnings.”

In addition, the modern information system has made it easier for misinformation to find audiences who are anxious for explanations. Recent distrust in traditional institutions such as NOAA has led people to make bad decisions or disregard information that could potentially save their lives. As Yotam Ophir, a professor at the University of Buffalo, states, individuals no longer “have the tools to identify truth and deception in such complicated topics.”

In an effort to fight these false narratives, government authorities and civil society organizations are now pushing back on disaster-related misinformation. For example, Representative Chuck Edwards conducted an interview where he challenged disaster-related misinformation. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) also has a rumor control page that identifies false information and provides reliable information. As FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell states, while it’s “really unfortunate that [people] continue to try to create this level of fear… we’re not going to let it deter us.”

Meteorologists are also developing new strategies to make sure their warnings are heard. Klockow McClain, a senior social scientist supporting the National Weather Service, suggested that meteorologists try strategies like humanizing scientists or messaging designed to “inoculate” against common types of misinformation. For example, John Morales, a meteorologist at NBC, has recently shifted his approach to incorporating climate science into his weather forecasts. While tracking the progression of Hurricane Milton on-air, Morales described the storm’s wind speed as it gained strength due to “record hot” waters in the Gulf as “just… horrific.” By admitting his horror at the mounting threat of global warming, Morales hoped to convey the scientific truth behind these extreme weather events. Perhaps this new approach will succeed in calming the storm of misinformation and restoring faith in public organizations.